Written By Alex Fierro

With the onset of the Covid-19 Pandemic in early 2020, those working in the realm of public history, like the rest of the world, confronted a number of daunting and unprecedented challenges. Foremost, the foundations of our work–in-person collaborative relationships–were put on hold to preserve the health of our friends, families, and communities. With our projects transformed by new modalities of instruction, the inability to meet face-to-face, and the stress and exhaustion brought by the pandemic, public historians found unique and innovative ways to reach out to their communities during this time.

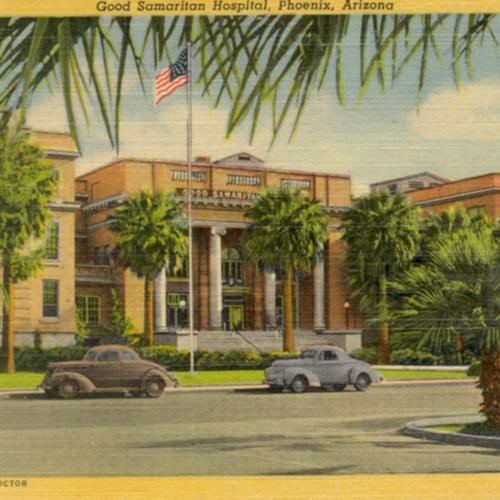

In Spring 2021, as our public history team collaborated with the Arizona Historical Society to document the history of the Banner University Medical Center in Phoenix (BUMCP), we documented these challenges head-on. Our small intern team of five students was given the opportunity to conduct oral history interviews with current and former staff, assist in the accessioning of BUMCP library materials, and collaborate on an in-depth report of our findings. Although this project might seem straightforward on paper, the pandemic caused a number of complications.

The most difficult hurdles to overcome were related to the oral history interviews, which had to be conducted over Zoom. Although many of us had become experts in Zoom by then, we came in with the understanding that not all of our interviewees would be equally knowledgeable or proficient in utilizing video communication software. As such, we did our very best to assist our interviewees and allocated extra time in our meetings knowing that technical complications might cause a 10–15-minute delay to the interview.

More importantly, we understood that we were talking to many healthcare professionals dealing with the devastation of the pandemic first-hand. These nurses and physicians, who were risking their lives to save others, were gracious enough to donate an hour of their time to speak with us about their past and present experiences, and for that, I know that the whole team who worked on this project are forever thankful. Due to these necessary time constraints, we were forced to simultaneously craft a condensed pool of questions while also developing thought-provoking queries that drew upon the unique life experiences of every individual. In addition, the team had to remain flexible, as many of the interviewees had ever-changing schedules and emergencies to address.

Despite doing this work virtually, we could sense the raw emotion and passion of all 29 individuals that we had to pleasure to speak with. Their ability to remain steadfast, united, and composed during this time was nothing short of inspiring. Although public history workers might not be able to directly save lives like these nurses and physicians, we can surely bring to light the histories of our local communities and why their lives matter.