Blog post by J. Nalubega Ross

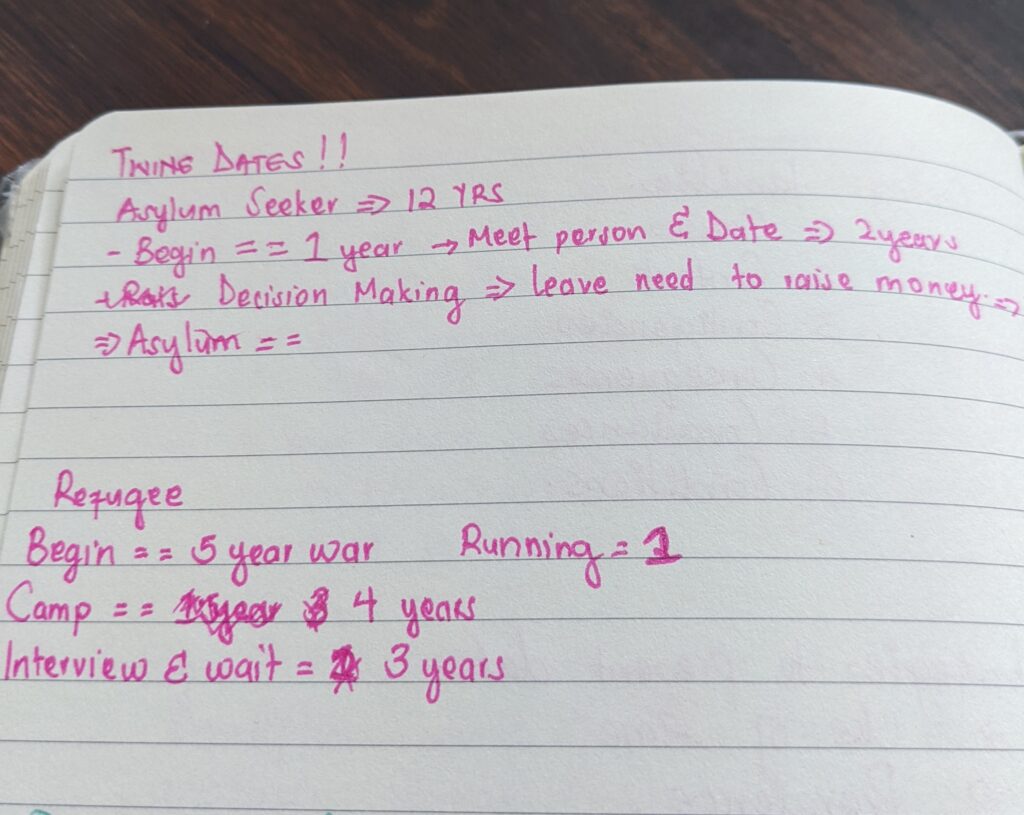

My little sister was standing over my shoulder, as I opened a version of this project. Being the brilliant tech security person that she is (yes, I am very biased but she is brilliant), I needed her coding expertise. As a doctoral student, studying African migrants and immigrants, I had wanted to show the temporal cost as well as the monetary cost of being either a refugee or an asylum seeker. I had chosen to use Twine, because it was, well, a free online app and did not have a very steep learning curve for someone whose coding expertise was limited to statistical analyses. Twine also allowed me the opportunity for me to give viewers a non-linear story that they could be a part of. With Twine’s “choose-your-own-adventure” style, I was able to give viewers the opportunity to walk in the shoes and make decisions as if they themselves were fleeing and seeking asylum. I also wanted to include a clock. The clock would show how much time in years it takes refugees to resettle and for asylum seekers to make the decision to seek asylum from other countries. So I sought the expertise of my sister because I knew I could explain to her what I wanted and she would make it happen. And I could call on my big sister privileges to side eye her if she did not do what I specifically wanted. As I was closing the multiple tabs and windows open on my screen — a mixture of news stories, journal articles, websites, and images that I was considering using, my sister made what was to her a throw-away comment.

“Wow, you read a lot of depressing stuff. That stuff will stick with you.”

I paused and responded,

“Yeah, that is part of my work.”

I continued to clear up my desktop and have her help me. But her words continued to bounce around in my head, days, weeks, and months after she said them. If you go through the experience you will notice that there is no clock. That is because I decided I wanted to spend time laughing with my sister instead of making us both work. I had not seen her for close to three years, so the clock was put aside and later completely forgotten. But as I consider this project again, I am reminded about her words. Yes, the work I read for this project did stick to me, and being a doctoral candidate, I can give you the whole spiel of what sources I used, why I used those sources, which theories I draw from etc etc. But it was when explaining to another family member that I realized how much the depressing stuff I’d read had stuck to me.

It is a snow day, and so no school for “The Radish”. The Radish is six and loves snow days because there is no school and there is snow to play in. And since we had no school, I say we because when she is out of school, I get half a work day at best, so we decided to go to the neighborhood cafe for breakfast. Tea and sausage roll for me, and a buttered English muffin with a side of bacon and a baby chino for her. As we waited for her order the cafe television was playing the international news and in between us discussing the free earl gray macaron the barista had given us and waiting, she turned to me and said;

“Everyone is talking about the war in Ukraine and Russia.”

And as I explained in six year old terms what was happening in Ukraine, I remembered the stories I had read for this project. The stories of desperation, loss, torture, and death that never made it to the final project. And they never made it to the project, because as Tuck and Yang (2014) remind us we can learn without serving up stories of pain. But though I chose not to serve up those stories of pain, I read, listened to, and viewed them. And in that moment with “The Radish” I remembered all of those stories. They had indeed stuck to me. And they were depressing. Just my sister had said before. And then I realized that we never really needed that clock after all. The clock would have been set to begin in the early 2000 and end in 2017 with Executive Order 13780[1] or as it was known as “The Muslim Ban”. But with the ongoing war in Ukraine, I realize that there is no need for a clock, because migration due to war and/or one’s identity does not stop in a given year. And so the clock is unnecessary but the experience is unfortunately still relevant.

[1] This order was reversed by President Biden.