This post by Glenn Summers delivers a tactile and analytical discussion of some sources on the 1913 strike at Leith Docks, a key event during the UK’s Great Labour Unrest. These sources were discovered during the Scotland Archives Experience in June 2024.

Archival research is largely conducted in order to reach nooks and crannies that the Hivemind of the internet has not yet absorbed. To me, almost equally important, it is about texture. Holding and examining original documents provides a tactile experience that communicates a reality the internet cannot provide. Physical documents, often with the earmarks of use, handled by the people involved and employed for their intended purpose gives one a sense of the reality of their lives. My project involved researching the violent, seven-week long strike at the Leith Docks near Edinburgh in 1913 as a prism through which to evaluate the tumultuous politics of the UK Leftist movements of the day and the 1911-1914 turmoil called the Great Labour Unrest (approximately 3000 strikes occurred in the UK during that period). Through the amazing resources of the National Library of Scotland and the University of Edinburgh Archives, following are three documents of interest I found as part of my research in Edinburgh whose physical aspects as well as their content conveyed information

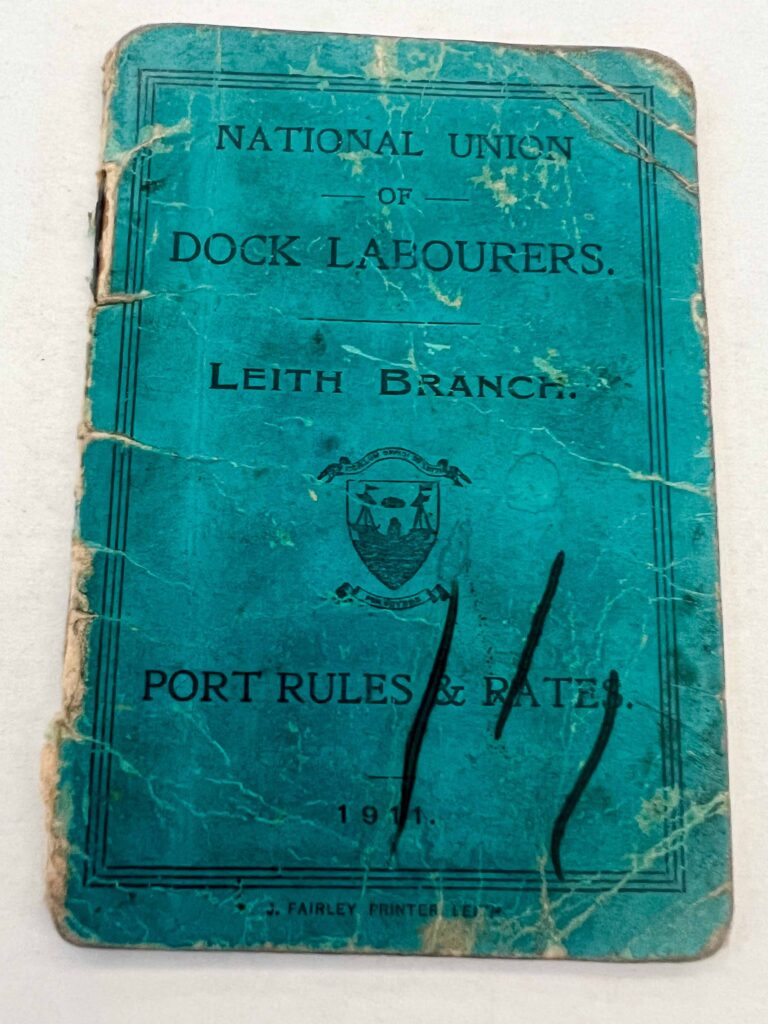

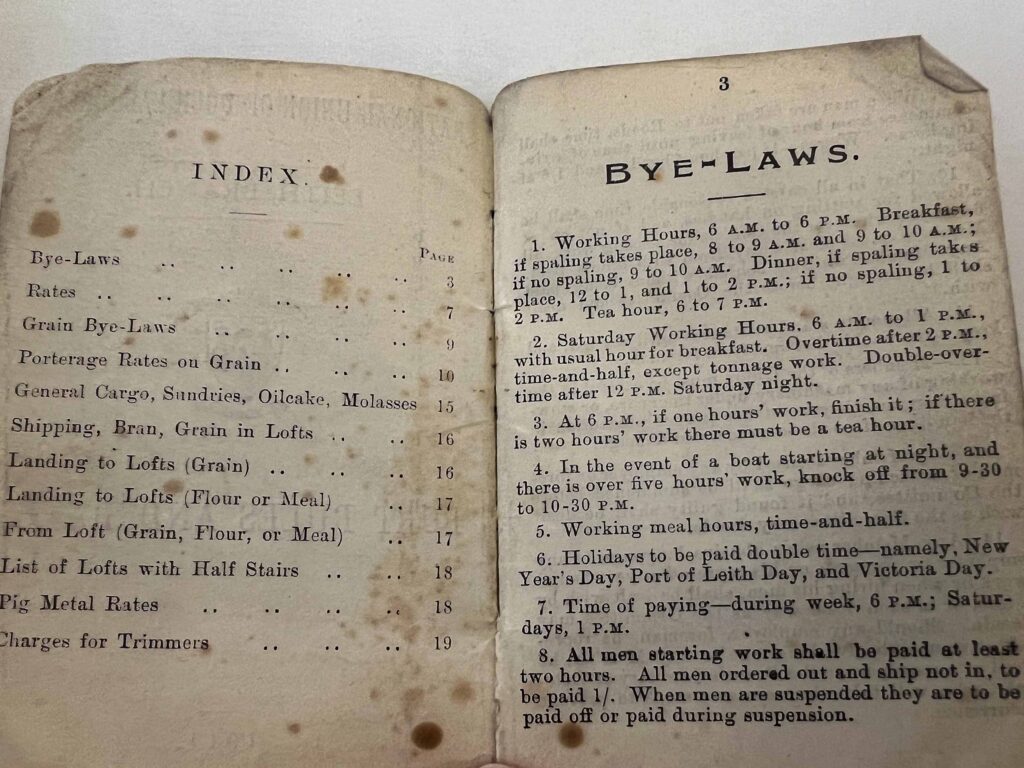

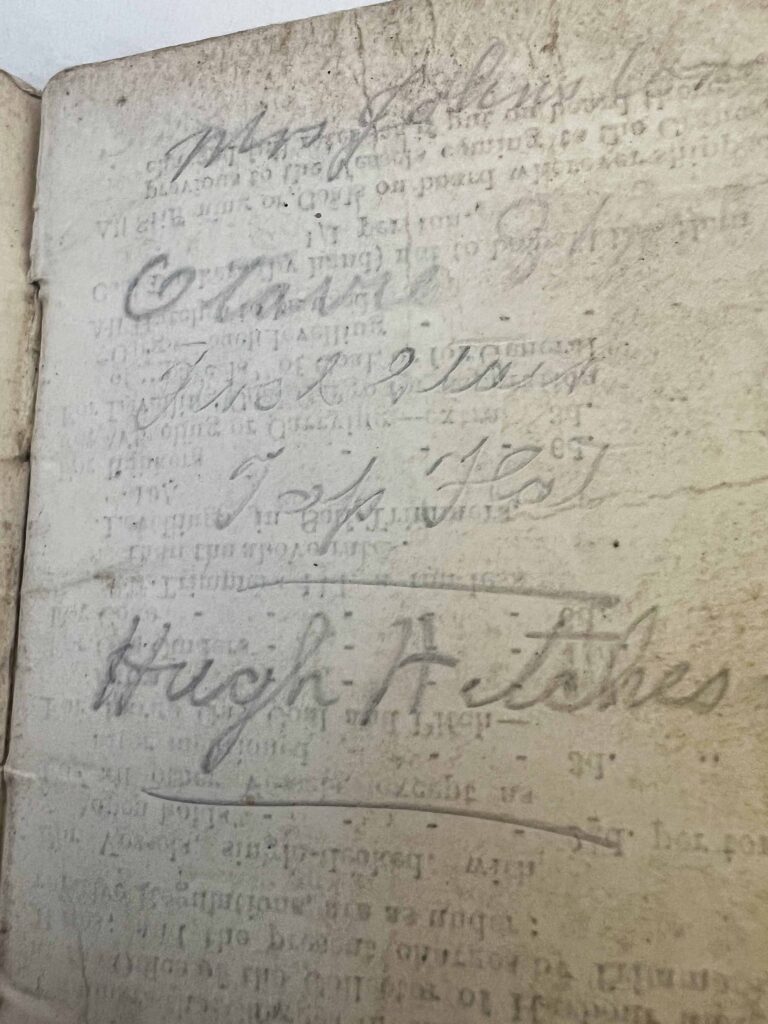

The National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL) represented the Leith dockers, and the first image is a booklet setting out the 1911 collective bargaining agreement between NUDL and the Leith Docks Employers’ Association. The wage rates are provided, and the “bye-laws” (British spelling) set the work rules that governed the workplace: starting, stopping, and break times (including “tea hour” if work goes more than an hour overlong), overtime pay, hazard pay, protection against unfair dismissal, and so on for several pages. The actual document is about three inches by five inches. It was intended to be carried in a worker’s pocket for ready access if there was a disagreement with a foreman or supervisor about terms of employment. The agreement constituted a small reservoir of power and protection for the worker against the worst abuses of the Industrial Revolution. This particular copy is dirty, dog-eared, cracked, well-thumbed, and on the inside back cover bears in bold strokes the hand-written signature of Hugh Hitches. Its heavy use and consultation, presumably by Hitches, reflects its importance.

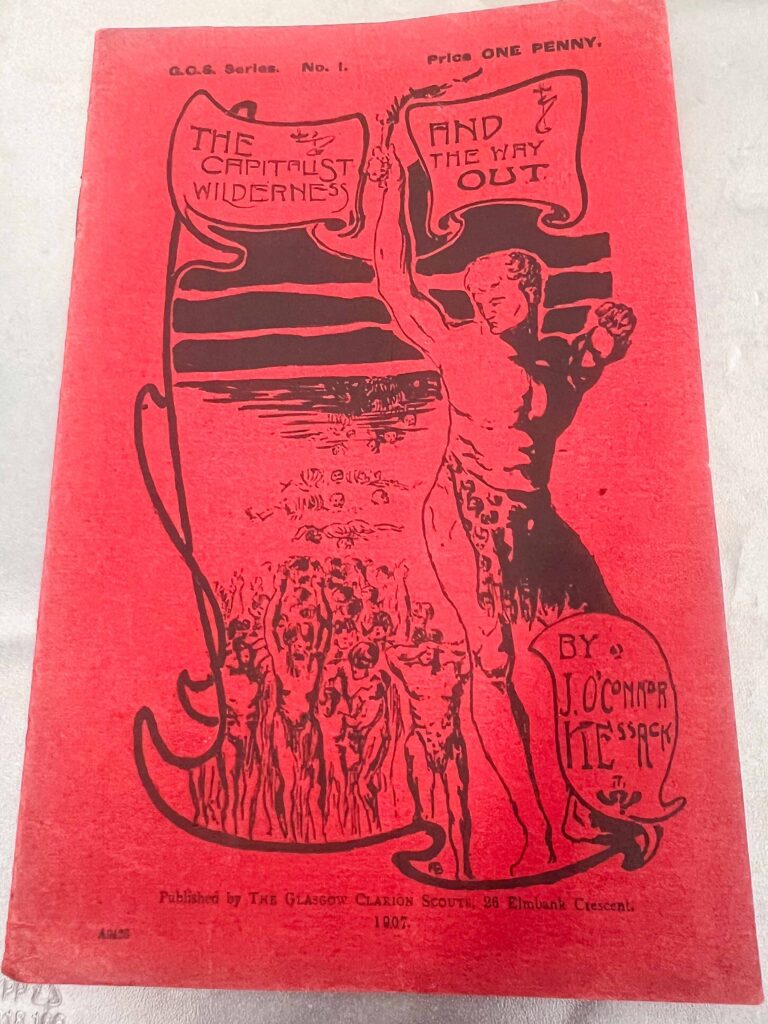

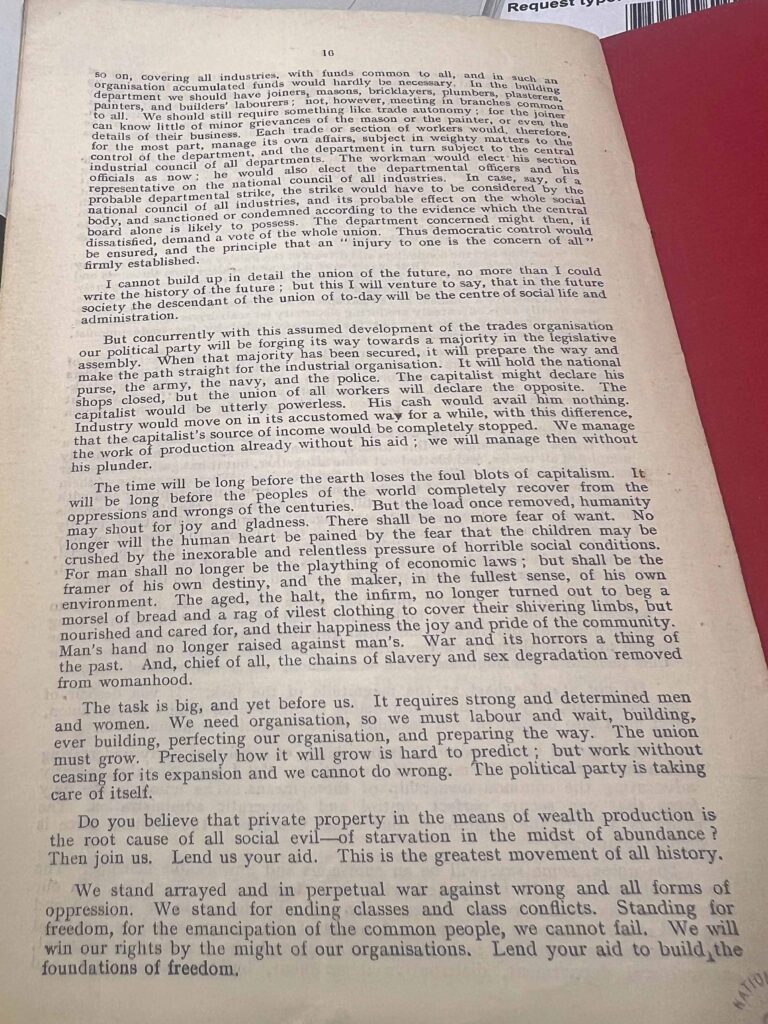

The archive also contains a 1907 pamphlet entitled “The Capitalist Wilderness and the Way Out,” written by James O’Connor Kessack, a NUDL organizer and the principal negotiator for the Leith dock labourers during the strike. Behind the somewhat lurid and amateurish cover and printed on cheap paper, the text provided a well-written, full-throated explication of revolutionary trade unionism, ideas then current in the related doctrines of theAmerican-born Industrial Workers of the World (“The Wobblies”) and the French-inspired movement called syndicalism. These movements expounded industrial unionization, direct action (as opposed to political action), and the general strike as the weapons that would ultimately lead to the elimination of the “foul blots of capitalism” and the creation of a utopian future. The pamphlet’s production values reflect limited resources, and the content a world view of struggle and hope as the radical unionists tried to get their message out—an exemplar of the state of UK revolutionary socialism in the early 1900s. Despite the limited resources, the message of radical unionism may have had a causal connection to the Great Labour Unrest. The extent to which these views expressed in 1907 guided Kessack himself in his involvement in the 1913 strike is an interesting and ambiguous question.

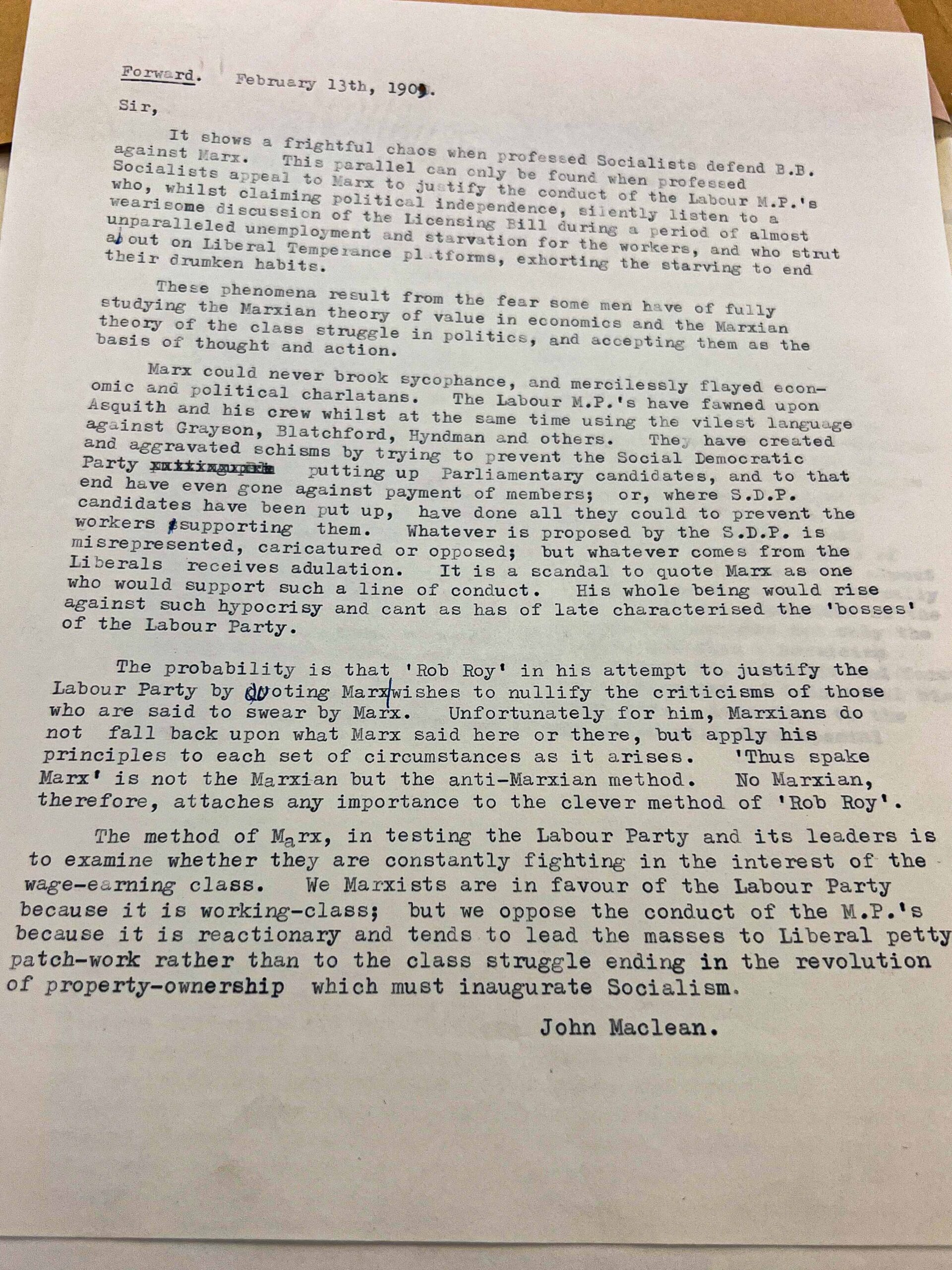

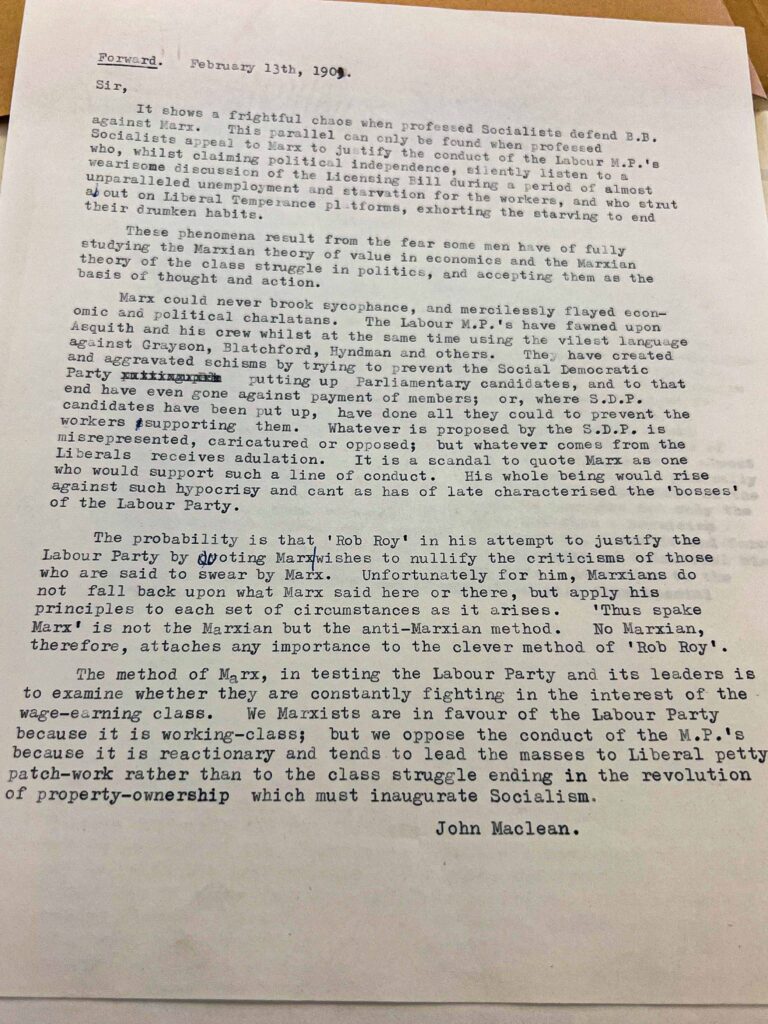

Finally, I found a 1909 typed letter from John Maclean to the journal Forward, the organ of the nominally socialist Independent Labour Party. Maclean was perhaps the most orthodox Marxist in Scotland. He formed his own Communist Party of Scotland and later was expelled as too extreme. After the October Revolution in Russia in 1917, he was named Bolshevik Consul to Scotland. So this guy had street cred. In the letter, he vehemently attacked the Labour Party MP’s for their compromising, accommodationist approach to Conservative and Liberal MPs. “Marx could never brook sychophance, and mercilessly flayed political and economic charlatans,” wrote Maclean, which was precisely what Maclean did in the letter as to the Labour MPs, his coreligionists under the umbrella of socialism. The letter is a good example of the fractiousness of the internal politics within the UK Left Wing. Forward published the letter at the time and the text of the letter is available online, yet there is something about reviewing the type-written letter itself that communicates his fervor in a way that a website cannot. You can almost feel Maclean pounding the keys in fury.

In my research, Hitches, Kessack, and Maclean were just three of the people I had the privilege of encountering through the works of their hands. The form and character of the documents themselves helped me in gaining a sense of the immediacy and urgency of the beliefs motivating them in those turbulent times.