Blog post by Monica Boyd, PhD, Humanities Lab

During the nineteenth century, an increasing number of cases were reported in Britain in which the murdered victim was decapitated and dismembered. I’ve identified nineteen through searching through multiple historical newspaper databases. Of those nineteen, sixteen were women or young girls, ranging in age from 7 to 55. Two were young boys between the ages of 8 and 10. Only one was an adult male and there is still debate today whether or not this case was a hoax.

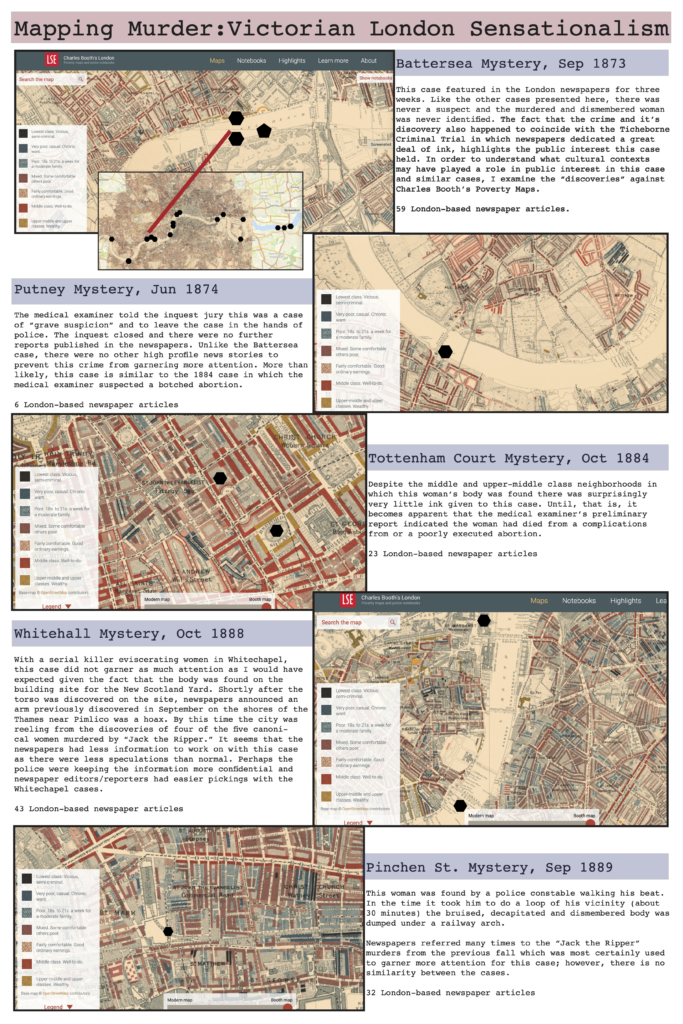

In some of the cases, the victim was identified and, in a few, a perpetrator apprehended. Seven women were never identified. Six of these occurred within 20 years, between 1873 and 1889. The majority of their bodies were found in London with one piece found in Rainham, a village to the east of London. The rest of their bodies were never found.

Studies have shown there is a cultural linkage between sexual violence and the murder of women by an assumed or known male suspect. In fact, this linkage goes back to a rape myth that emerged in the discourse surrounding the rape and subsequent murder of Mary Ashford in 1817 as identified by Anna Clark (Women’s Silence, Men’s Violence, Pandora Press, 1987).

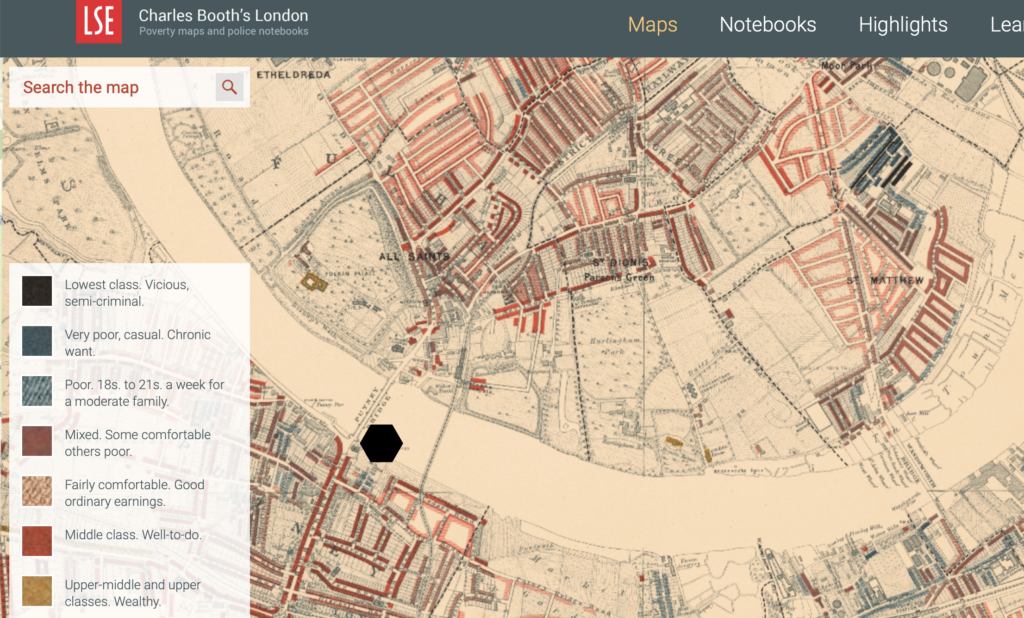

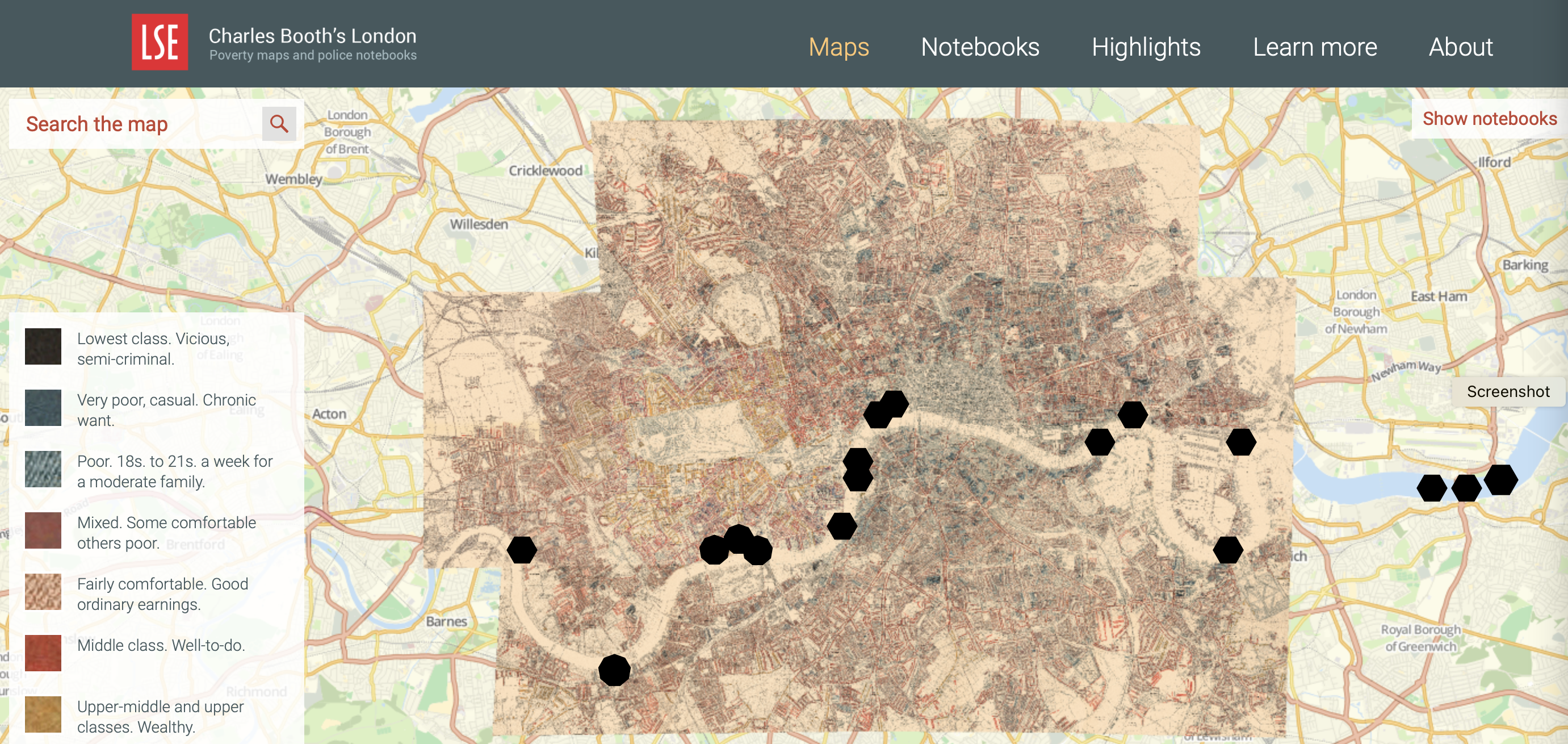

Dismemberment is a gruesome crime. It also muddled tracking the different cases as the perpetrator(s) scattered the bodies’ parts throughout the city. In order to help myself keep track of the cases I created a Google “My Maps” along with other visual guides like forensic body diagrams. In a larger work I analyzed the newspapers for thematic codes about the victim, the suspected perpetrator(s), the crime itself, use of affective language, etc. to glean a sense of how the cultural linkage between sexual violence and murder presented itself during this time period. While there was no evidence of sexual violence having occurred within the newspaper accounts, the reporters and editors treated the cases as if there had been, for the treatment of the body post death certainly eschewed culturally gendered-sexual mores.

The Digital Project Showcase during Humanities Week 2021 gave me the opportunity to focus on the maps and ask a question that’d I’d been wondering about for a while: what can we learn about the newspapers reaction to the crimes by comparing my Google map to Booth’s Poverty Maps? The answer, I learned, was complicated.

The case which was the most sensationalized in the local news (1873) was first discovered near more financially well-off communities. I’d suspected that the more sensationalized cases would follow a similar pattern. However, in a later case (1884), where the victim was found in an upper-middle-class neighborhood, the story disappeared from newspaper reports immediately once medical officials discovered the woman had an abortion. The fact that the woman had an abortion was so taboo that the story was suppressed despite the initial desire to capitalize on a scandal. The two cases that follow the infamous 1888 “Autumn of Terror,” received plenty of ink despite the crimes occurring in lower-income neighborhoods. This was done in order to exploit the anxiety and horror generated from the five women killed by “Jack the Ripper.”

Because of cultural taboos and shocking contemporaneous events, the original hypothesis about sensationalized crime and environment was indeterminate with this sample. Sensational newspapers were quick to report the story when a potential for increased sales was present. However, social proscriptions were a factor for editors; when did a case cross the line from sensational to unsellable? Still, superimposing the data from these crimes onto Booth’s Poverty Maps provides more context for analysis, which is always beneficial, and the exercise proves useful to anyone seeking a greater understanding of historical culture.