John Cardoza is a retired attorney and 2023 online MA graduate. After an initial, unfinished foray into graduate history at UCSB in the late 1970s, he attended law school at UC Davis and was employed in Ventura County as a prosecutor and family law attorney. He currently contemplates pursuing his PhD.

Below, he reflects on his research experience in Edinburgh, where archival research and physical documents provided a deeper connection to historical lives than online sources. As happens in the archives, researchers often have to shift their focus. Cardoza experienced this, pivoting from a project on Edinburgh’s New Town to comparing the motivations behind the development of Pulteneytown and Fochabers, two planned villages from the 18th century.

By John Cardoza

Our trip to Edinburgh was an education on so many levels, and figuring out the mechanics and rudiments of archival research was but one component. Sifting through letters, manifests and contracts from late eighteenth-century Scotland exhilarated me, and although I’ve finished the MA program, I never felt more like a historian. Holding and reading original documents created a connection with people’s lives that published and online reproductions can’t equal. While I spent a day in the City of Edinburgh Archives and another in the Collections of the University of Edinburgh Library, I spent most of my time in the Historical Search Room of the National Records of Scotland. Here, I learned valuable lessons about keeping an open mind about my research and being amenable to modifying a topic to focus on a specific historical question. I realized that sources and time sometimes mandate change. This proved a challenge.

To access the NRS Search Room, I needed a Reader’s Ticket, which requires some online prep work and a passport photo. On my first foray into the Research room, I was vetted by the archivist on duty. This vetting proved to be a boon for me and recalibrated the direction of my research. The archivist, Alisyn, asked about my research topic, which, at the time, was the mid-late 18th-century development, building and maintenance of Edinburgh’s New Town, which started in 1767. Alisyn informed me that New Town was the most prominent manifestation of hundreds of “planned villages” that proliferated Georgian Scotland. For example, Alisyn cited Pulteneytown, a planned fishing village developed and built in the late 18th and early 19th century.

“It might be nice to make a comparison,” she suggested as she printed out a list of documents about Pulteneytown that she thought might be helpful.

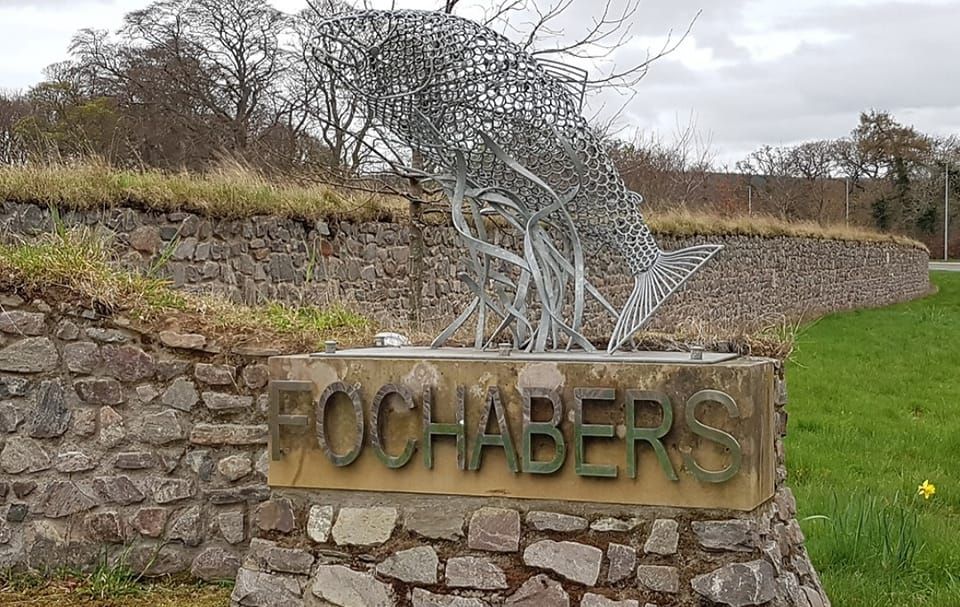

Fochabers, Scotland is a village in the Parish of Bellie in Moray.

Examining 250-year-old maps, letters, writs, contracts and house plans from New Town Edinburgh and Pulteneytown, I understood the need to learn more about what motivated the “planned village” movement and sought primary sources to help explain it. During this search, I found another new village, Fochabers, developed to replace an older village by its founder, the intriguing and eclectic Alexander, Fourth Duke of Gordon (Gordon). Unlike the New Town, the administrative product of Edinburgh’s Town Council, or Pulteneytown, developed by the British Society of Fisheries, Gordon built the new Fochabers for his economic benefit, partly to generate income to improve his castle. An entrepreneur in the truest sense, Gordon wielded almost plenary power in his region, responsible for law enforcement while engaging in diverse interests like shipbuilding, dog breeding and village founding (he built three villages with varying degrees of success). Gordon proved to be a challenge to my research’s focus—his outsize impact on his region distracted me— and I had to force myself to concentrate on planned villages rather than one village planner. Had I discovered Gordon a few days earlier, I would have reconfigured my research, focusing on him.

After discussions with our professors, I decided to scrap New Town altogether and instead opted to analyze the common elements and disparate motivations for developing Pulteneytown and Fochabers. While both share vestiges of the Scottish Enlightenment’s “era of improvement,” the differences in their founders will hopefully provide a complex and engaging study.