Blog post by Clinton P. Roberts

As the nightly news rattled off statistical numbers, my grandmother sat quietly in her house, mourning a loss, unable to see her husband’s grave. Her daily visits to the cemetery marked an otherwise unbroken routine for over five years. She felt solace in the routine. As COVID-19 constrained daily life, rural lives were affected in quiet ways. The Journal of the Plague Year captures those stories in the “Rural Voices” collection, inspired by the local community of Blanchard, Oklahoma. This collection counterbalances the otherwise dominant role of metropolitan areas in national media. They offer a glimpse of the uniquely rural experiences of loss and hope during the pandemic. After three months working on the collection, I’ve learned that rural areas like Blanchard are processing the pandemic through three distinct realities: adaptation, quiet voices and the common good.

Adaptation

These quiet stories may never make the national news, but their value remains. They cover the local community of Blanchard and capture dozens of events. These events range from a church’s first virtual service[1] to an encouraging graffiti message,[2]. All were centered on the rural experience. Blanchard expressed, among its greatest strengths, adaptation and determination in providing a drive-thru graduation and outdoor prom for high school seniors.

Graffiti. Photo courtesy of Clinton P. Roberts

Blanchard Outdoor Prom. Photo courtesy of Clinton P. Roberts

Grandmother. Photo courtesy of Clinton P. Roberts

In one interview, high school senior Kris McDaniel offered his thoughts on having an alternate graduation and prom. In a message intended for his future grandchildren, Kris poignantly stated, “value your time… I took it all for granted.”[3] At only eighteen years, his wisdom weighs the value of loss, even as he thanked his community’s generosity. The historic value lies in the effect of breaking tradition within rural communities. The abrupt, dipropionate way a pandemic disrupts, ripples across all facets of daily life.

Quiet Voices

The collection preserves memories like Kris McDaniel’s high school story, providing a lasting voice to an otherwise silenced perspective. Historians such as Michel-Rolph Touillot addressed the idea of historical silences with heralded success, questioning the “uneven contribution of competing groups and individuals who have unequal access to the means for such production.”[4] The “Rural Voices” collection provides a record of rural perspectives in a national historical archive, thereby offering contribution and access, providing space for future listeners to hear their quiet voices.

The Common Good

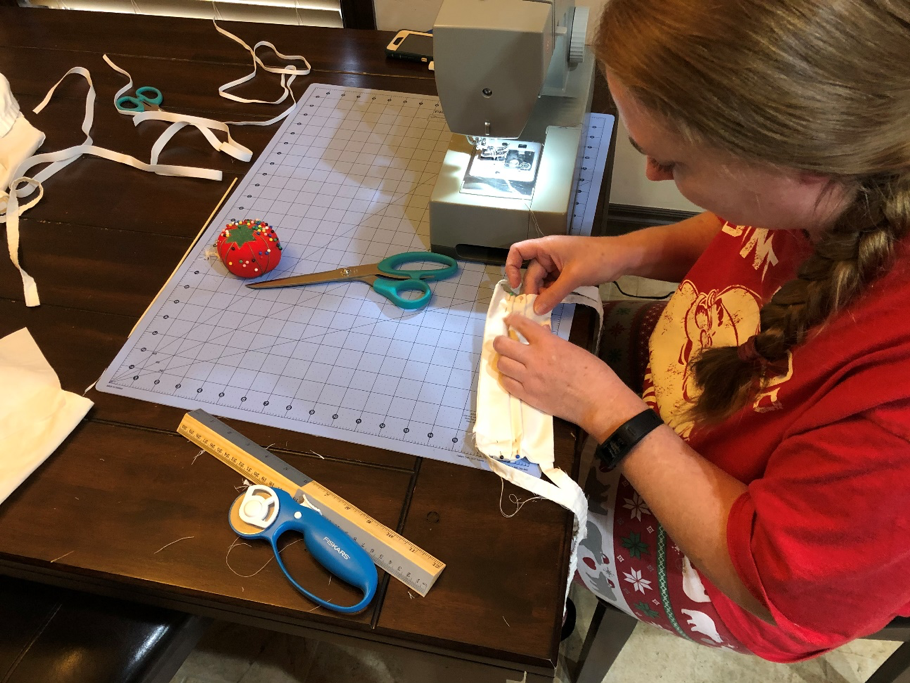

The collection also shows the ways that members of Blanchard implement the concept of “The Common Good,” into their everyday lives and decisions.

Face masks reveal some of the nuanced values of rural communities. An oral history interview with Phillip Hoile captures this. Discussing protective masks, Hoile states, “I don’t need a mandate,”[6] but then later reiterates that he does wear a mask because, “it’s common courtesy and you know let’s, let’s do what’s better for everybody until this thing blows over.”[7] His opinion could otherwise be construed as skepticism, but is actually an often-observed rural perspective – local community opinion and self-determination are valued above outside influences. Masks have value, because they protect the community.

We will get by

[1] Clinton P. Roberts. “Rural Oklahoma Church Members Attend Online Services During COVID-19.” Journal of the Plague Year, Rural Voices Collection, May 28, 2020. Accessed August 2, 2020. https://covid-19archive.org/s/archive/item/18378

[2] Clinton P. Roberts. “Message of Hope Left on Control Box Near a Congressional Medal of Honor Recipient Memorial.” Journal of the Plague Year, Rural Voices Collection, June 14, 2020. Accessed August 2, 2020. https://covid-19archive.org/admin/item/20634

[3] Clinton P. Roberts, “Interview with Kris about Being a Senior in High School and Experiencing Distance Graduation During COVID-19”: Journal of the Plague Year, Rural Voices Collection. Audio. May 27, 2020, https://covid-19archive.org/s/archive/item/18366 (accessed August 2, 2020).

[4] Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), xix.

[5] Marisa Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 4.

[6] Clinton P. Roberts, “Phillip Hoile Oral History, 2020/07/25”: Journal of the Plague Year, Rural Voices Collection. Audio. July 25, 2020, https://covid-19archive.org/s/archive/item/25029 (accessed August 2, 2020).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Clinton P. Roberts. “Grandmother Grateful for Opportunity to Visit Husband’s Grave for Memorial Day During COVID-19.” Journal of the Plague Year, Rural Voices Collection, May 28, 2020. Accessed August 2, 2020. https://covid-19archive.org/s/archive/item/18389

[9] Clinton P. Roberts, “Phillip Hoile Oral History, 2020/07/25”

[10] Ibid.

[11] Clinton P. Roberts. “Message of Hope Left on Control Box…”